By David Kroman

A month after a minimum wage for gig-based delivery workers took effect in Seattle, lobbying over the new requirements — both for and against — has kicked into a higher gear, a reflection of driver frustration with some of its ripple effects and the changing political climate in Seattle.

Though the law is still in its infancy, its future is already an open question. All but two members of the council who voted in favor of the law have either left willingly or been voted out, and much of the new council has taken a more skeptical view of envelope-pushing labor regulations.

Companies like DoorDash, Instacart and Uber Eats have gone on the offensive, scaling back certain aspects of their platforms and adding a $5 delivery charge they say is the result of the guaranteed pay. DoorDash called the minimum wage, along with new requirements surrounding when a driver can be blocked from the platform, “extreme.” The law is leading to fewer trips, it contends, hurting restaurants and leading to less total pay for drivers.

“We hope the newly elected City Council will come back to the table and make things right,” the company said.

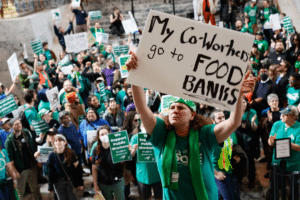

The labor advocates who passed the law now find themselves on the defensive, a dramatic change from the broad support they enjoyed from past councils. On Thursday, the group Working Washington, a 501(c)(4) organization with close ties to the Service Employees International Union, hosted a rally in favor of the law complete with a skit featuring a monocled money baron.

They’ve countered that the law represents a bare minimum for what delivery drivers should be guaranteed while working in and around Seattle. Though they acknowledge trips are down — and that some drivers may in fact be earning less than before — they say such an outcome was not an inevitability and instead the result of the companies’ resistance to paying better wages.

“Workers’ day-to-day incomes are on the line because of the app corporations’ unwillingness to just pay workers a living wage and make a smart business decision that doesn’t affect customers and small businesses,” said Hannah Sabio-Howell, communications director for Working Washington. “Instead, they’re making a political decision.”

Passed in 2022, the law sets a floor for drivers who work for delivery companies like DoorDash, Instacart, Grubhub and Amazon Flex, which rely on independent contractors not subject to the city’s nearly $20 minimum wage. It requires the companies to pay at least 44 cents per minute, plus 74 cents per mile during orders, or a minimum of $5 per order — intended to at least match and possibly exceed the city’s minimum wage.

The city, and then the state, previously passed separate legislation setting a minimum wage for drivers with Uber and Lyft.

Seattle’s regulatory efforts could set a precedent, good or bad, for other cities looking to hone the amorphous landscape of contractor-based delivery services. Though several cities have sought to regulate Uber and Lyft, few, if any, have done so for delivery services.

“I don’t know of any other state or locality that has done broad gig work minimum pay,” said Seattle University law professor Elizabeth Ford.

The challenge of setting a minimum wage for drivers is they are not paid by the hour, requiring Seattle to come up with a formula based on estimated minutes worked per hour that could come close to mirroring what employees are guaranteed.

The companies say the current rates equal out to more than $26 an hour, which would comfortably exceed minimum wage. Working Washington counters that those calculations fail to consider dead time and wear and tear on personal vehicles.

There is agreement, however, that the delivery landscape looks different now than it did before the minimum wage. Kimberly Wolfe, a driver and organizer with Working Washington fighting in favor of the law, has seen trips disappear, particularly because she used to drive for Shipt, which pulled out of Seattle entirely after the law took effect. She knows other drivers are frustrated as well.

The question is one of blame, and Wolfe puts it squarely on the companies.

“If it wasn’t the app companies throwing a wrench in the works, it would have been perfectly fine,” she said. “But they’re looking at the long term; they don’t care.”

The companies, meanwhile, counter the delivery charge is a predictable outcropping of a disrupted market.

“What we’re concerned about is that the law is having the exact unintended consequences that we told the council in 2021 and 2022 and 2023 would happen, that consumers would stop using the services and it wouldn’t matter what you pay them per trip,” said Michael Wolfe (no relation to Kimberly), executive director of Drive Forward, a 501(c)(6) drivers’ association that gets money from some of the companies.

He said some members are reporting losses of up to 50% of their income. The exception is Amazon Flex drivers, who are given predetermined routes and are earning significantly more. But food orders, particularly small ones for one or two people, are down.

Clouding the debate is resistance on the part of the companies to release internal data, which they protect fiercely as trade secrets. DoorDash, for example, has reported a net loss of $1 million in revenue for local restaurants in two weeks in January but has not disclosed how it calculated that loss.

Steve Marchese, director of Seattle’s Office of Labor Standards, said the onus is on the companies to explain their surcharges.

“I think there’s an opportunity to turn to these companies to justify these costs,” he said.

Mayor Bruce Harrell has voiced continued support for the minimum wage after signing it into law in 2022.

Members of the new City Council have not said how it will approach the regulations. But Council President Sara Nelson has made clear it’s an area she’d like to revisit. In recent weeks, she’s met with both Wolfe of Drive Forward and lobbyists for DoorDash, according to visitation logs published on the city’s website.

“I believe that we do need to look at our policy options and then see what is possible,” she said in a recent interview.

Whether it’s a proposed update to the rates or a full repeal is unclear, but in his conversations with Nelson, Drive Forward’s Wolfe said he got the sense she wanted to move quickly.

For his part, Wolfe doesn’t support striking down the whole law, arguing instead for a more deliberative process as the city collects data on its impact in the coming months.

“I think there are plenty of things in this law that are worth keeping,” he said.

But Working Washington is resistant to changes. Sabio-Howell drew a parallel to the city setting a $15 minimum wage, which initially set off alarm bells for some businesses but has since become normal and expected.

“I think the law just needs time to be implemented,” she said. “It would be unheard of and poor policymaking to repeal or rollback of minimum wage law for low-wage workers.”