Even when writers have good intentions, they can’t escape gender bias, a new study shows.

Even scientists find objectivity to be tough. Because of unconscious gender bias, they are twice as likely to write outstanding letters of recommendation for men than for women, according to an extensive new study of recommendation letters in the geosciences published last week in the journal Nature Geoscience.

What many found most surprising was that it didn’t matter if a woman or a man wrote the letter: the bias stayed the same.

Glowing letters were often packed with language the researchers identified as “excellent,” describing a candidate as a “rising star,” “superb,” or “brilliant.” Women were more likely to get “good” letters that characterized them as “hardworking” and “diligent.” Yet men and women were equally as likely to get “doubtful” letters.

Kuheli Dutt, a co-author of the paper and the diversity chair at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, noted in explicit terms; “This is implicit bias. If there was conscious sexism, women would have a larger number of doubtful letters.”

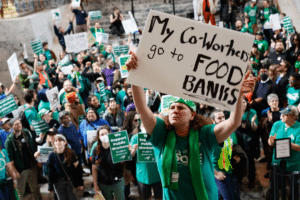

The research, which examined letters written for newly minted PhD students, follows several other studies of hiring in the sciences that verify the pervasiveness of “implicit or unconscious bias,” or the problem where humans unknowingly make certain assumptions about race and gender that can influence perception and action. The fact that scientists are affected by implicit bias does not mean they’re sexist ― after all, the bias cut across women and men alike. Rather, it confirms that their brains have developed certain associations they don’t even know about: men are more likely to be seen and described as aggressive leaders and women as diligent nurturers.

Implicit bias emerges in multiple ways in our culture ― in policing and education for example, where the overwhelming evidence shows that black people get stopped by police more often and black children are suspended more frequently, even though they are a significantly smaller portion of the U.S. population.

Unconscious bias has become such a big issue that companies, like Google and Microsoft, are teaching employees about it in an effort to get more women and people of color into their work forces. They’ve even developed software to help hiring managers cut implicit bias from their job listings.

This new research on letters of recommendation is significant because these letters are essential to getting doctoral students into their career paths.

The researchers examined 1,224 recommendation letters for postdoctoral fellowships in the geosciences. These were collected from 54 countries during the years spanning 2007–2012. They removed gender identifiers before sorting the letters into the three categories. Excellent letters were absolute raves, and said things like “X is exceptionally talented and brilliant, and has the potential to become an internationally famous scientist” and “X is a rising star of the 21st century in this field.”

The good letters clearly stated that the candidate was very solid if not a star: “X is hard-working, sincere, intelligent and very motivated” and “X has a good foundation in this field since s/he took many courses in it.”

The doubtful letters showed that recommenders were not supportive of the candidates, with language like “X is very set in his/her ways and does not accept advice or critique from his/her colleagues.”

Of course implicit bias in hiring goes well beyond fields in the sciences. Other researchers have examined interview conventions, the promotion process and performance reviews as areas that also favor men and need attention.

Once again, it’s worth emphasizing, as the Lamont study researchers do, that this kind of bias is unintentional. For that reason, it can be even more difficult to identify and eradicate ― it’s immensely challenging to fix a problem of which few are aware.

“We aren’t trying to assign blame or shame,” Dutt said. Hopefully the research will start a conversation and raise awareness, she said. It would be productive if, even privately, people who write these letters start looking at the language they use for men and women ― just to get a better sense of what’s going on. “It’s a larger problem.”