American businesses have found themselves as a crossroads.

One path prioritizes profitability for shareholders, oftentimes at the expense of the natural environment, workers’ rights and even executive wellness. The other track, which a growing number of companies are beginning to follow, evaluates all stakeholders impacted by a firm’s operations — not just those with a financial interest. It’s what sustainability and social justice activists call the “triple bottom line.”

Yet if companies are more and more motivated by their social mission, should they also recruit workers driven by similar values and goals?

That can be tricky. A mere 28% of American workers — just 42 million out of 150 million people – report that they find meaning in their lives through their profession, according to a recently-released report . The study emerged from a 36-question online survey of more than 6,332 adults this past summer.

That’s a pretty small pool to choose from.

As explained by Anna Tavis, author of the report and an adjunct professor at New York University’s School of Professional Studies, “The most important objective of any employer is to bring in people who have that purposeful gene, that purposeful orientation. They need to be identifying and looking for those people.”

Both anecdotal reports and hard data show that purpose-oriented workers are generally stronger employees since they are motivated by the significance they find or invest in their work, rather than simply being driven by paychecks, status or fancy jobs titles. This point was confirmed by the study’s other co-author Aaron Hurst, CEO of the firm Imperative, which helps companies identify such purpose- or value-driven candidates.

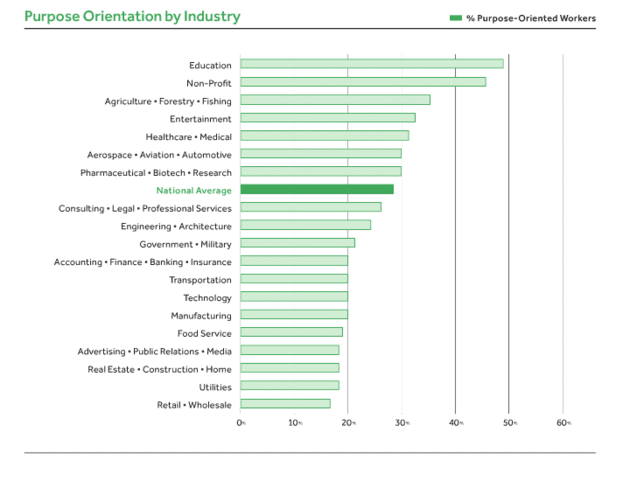

Of the fields examined in the study, education and nonprofit work polled as the two most purpose-driven, although neither of them had a majority of workers finding meaning in their jobs.

Among individual workers, artists and entertainers rose to the top of the list, with 55% reporting they felt driven by purpose. At the bottom of the list were operators and laborers.

Hurst explains that his company offers evaluations to help hiring managers identify behaviors that indicate purpose orientation. But, in the absence of such assessments, he recommends looking at three different areas of interviewees’ future and past career plans:

1. Retirement: “Purpose-oriented people don’t think of retirement as a desirable outcome,” he said. “They see life as doing always some kind of work and providing value to the world.”

That isn’t to say companies should only hire workers who never want to stop working. But if a potential employee’s main motivator for going to work every day seems to be keeping warm the nest egg he or she hopes to retire on, that person may not value the meaningfulness of work in the moment.

2. Work history: “What changes did they make, and why?” Hurst said. “Were they trying to make more money and get a bigger title? Or were they looking to maximize their impact?”

3. Friendships in the office: “A lot of purpose-oriented people tend to make a lot of friends at work,” he said. “If you’re interviewing someone who is still in touch with people from previous jobs, you’ll start to see some people driven by purpose.”

But there’s more at play here than an employer being highly selective during the hiring process. Purpose-driven people gravitate toward companies and organizations with a social mission, so if a company wants to attract purpose-driven workers, it must find its own purpose.