As the farm labor shortage grows worse, some farmers are turning to automated harvesting machines and other robotic technology to carry out the tasks of pruning, seeding and weeding.

Robotic harvesting vehicles are currently being piloted in Florida and California to pick strawberries and replace labor-intensive tasks typically done by dozens of farm workers. In addition, the technology is being tested in apple orchards, and other efforts are underway to create small field robots that would attack weeds and manage other farm work.

Giant agricultural companies are pushing for robotic solutions by investing in technology firms and testing of next-generation equipment on their own farms. “We’re seeing more and more of a move towards just technology in general, whether it’s robotics or mechanization,” said wine grower Ryan Jacobsen, CEO of the Fresno County Farm Bureau. “We’ve seen some incredible improvements there, and for us to remain competitive in California just because of so many areas of cost and the lack of needed individuals to help us bring in the harvest we’re going to have to rely upon this technology.”

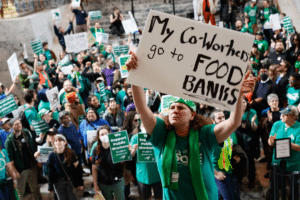

Farm Labor Shortage

2017 was an especially rough year for farm labor in the heart of California’s agricultural region, the San Joaquin Valley. In fact, it was the tightest year farm counties have seen in a decade, according to industry executives. The state’s $45 billion agriculture industry grows nearly 50% of the fresh fruit, vegetables and nuts in the U.S.

For the last generation, California’s agricultural workforce has been made up of mostly immigrants, many without documentation. As Daniel Sumner, a University of California at Davis professor of agricultural explains, the flow of farm workers has been consistently dropping with beefed up immigration sweeps by the federal government.

And where human workers have become scarce, small robot fleets are now operating in swarms, a system known as “Xaver” from AGCO. This technology carries out high-precision farm tasks like corn planting. The autonomous vehicle concept on farms also be used for fertilizing. The company’s website said the robot can plant “round the clock, 7 days a week, even in conditions that conventional machines find difficult.”

“What I tell people is, we’re like self-driving cars,” said Florida strawberry grower Gary Wishnatzki, co-founder of Harvest Croo Robotics, a Florida-based robotic harvesting company. “We don’t have to be perfect. We just have to be better than the humans—and believe me humans damage a lot of fruit, too, when they’re picking and packing it.”

Strawberry-Picking Robots

Wishnatzki, who is also CEO of Florida-based Wish Farms, said a single strawberry-picking robot could harvest a 25-acre field in just three days, replacing the work of nearly 30 laborers.

Harvest Croo’s robotic harvester is already working the fields in Florida, where it employs vision sensors and software to scan plant grids and identify ripe berries. It is also equipped with features designed to avoid bruising the soft fruit.

Similarly, Spain-based Agrobot has been testing a berry harvester in Driscoll’s fields in Oxnard, California. Driscoll’s grows berries in nearly two dozen countries.

Labor costs for the American strawberry industry come close to $1 billion annually, and the new equipment is poised to be competitive with human harvesting costs.

Nonetheless, experts predict that automation won’t steal all the farm jobs, even for rather repetitive tasks. But it could prove a disruptive technology for folks in the farm sector who resist change. And it will surely change the way traditional growers operate. Similarly, it could require farmers to employ highly skilled people with software skills to operate and maintain the advanced technology.

“I don’t think automation or robotics will ever replace the farm worker,” said Tom Nassif, CEO of Western Growers, the trade association for agricultural producers in the West and Southwest. “It will certainly cut down on the number of people we need to plant, thin and harvest our crops.”

Slicing Labor For Lettuce And Tomatoes

Some sectors that dove head-first into mechanical harvesting several years ago are already cashing in on the benefits. For example, the task of processing tomatoes—used for everything from soups to spaghetti sauce—has experienced a 90 percent labor savings over hand harvesting, according to the California Farm Bureau Federation.

“We have put in mechanized or automated solutions to reduce our dependency on heavy manual, hard-to-get labor,” said Bob Whitaker, chief science and technology officer of the Produce Marketing Association, a trade group representing global produce companies. He said the technology is getting faster, more compact, and cheaper, so it’s better able to address labor problems in agriculture.

For example, Whitaker explains a new platform to harvest lettuce that cuts the head using a water blade instead of the traditional method of using hand labor and a metal knife.

Indeed, a mechanical lettuce harvester with a water jet is made by California-based Ramsay Highlander and costs around $750,000. That may sound pricey, but it can pay for itself within the first year on big farm operations since mechanized harvesting requires only a small fraction of the labor typically needed for such tasks.

“I’ve been approached by people in other commodities, such as cantaloupe, table grapes, tomatoes—all the fresh market vegetables like that to address this robotics mechanization,” Maconachy said. “We’re currently looking into starting up a project for the table grape industry.”

Grape-Gobbling Machine

Meanwhile, mechanical has moved into the wine grape industry of California’s Central Valley. The work of one machine in large-scale vineyards can pick 20 tons of grapes an hour and replace work normally carried out by 30 or more human pickers.

Manufacturers of those grape harvesting systems claim their technology can remove 99 percent of the leaves and other unwanted debris picked in vineyards to produce cleaner fruit and save time.

Nearly 80 percent of the wine grapes from California are now harvested by mechanical harvesting, according to the California Association of Wine Grape Growers. The cost of mechanical picking is less than half that of hand-harvesting and is expected to become even more attractive to employers with California’s minimum wage set to increase to $15 per hour in 2022.

Washington is another state that uses mechanical harvesting of wine grapes to compensate for seasonal labor shortages, even those some of the machines cost nearly $400,000. Washington ranks as the second-largest wine producing state after California.